Equal Power

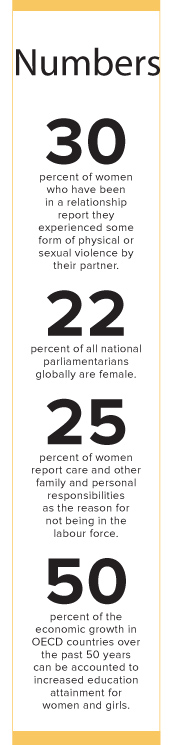

Gender inequality is stubbornly persistent. Even today, despite best efforts, it remains strongly weighted in favour of men. Jo Swinson is a mother, a feminist, a member of parliament in the UK, and now an author, and she is making a difference to gender equality.

In 2017 sexual harassment allegations filled headlines and the pay gap between men and women grew. It’s safe to say it was a tough year in the fight for equal rights and treatment. There were positives to come out of it, however, as people fought tirelessly toward gender inequality. Jo Swinson, current Deputy Leader of the Liberal Democrats and brazen feminist, is one such woman. She sees gender inequality everywhere from the shows we watch on prime time TV to the story books we read to children. All of this is recalled in her book, Equal Power, which not only discusses her experiences with inequality but is a call to arms for actually making change happen: “Instead of despairing at the state of the world, let’s roll up our sleeves and change it’, she writes in the opening chapter.

Swinson is not just talking, and in this case writing, about making a change to gender inequality. She has already taken action. From 2015, she made it possible for parents to share their eight weeks of parental leave. The former Equalities Minister also ensured large employers have to publish their gender pay gap data including mean and media pay gaps, number of men and women in each salary quartile and gender gap in bonuses. The UK is now one of the first countries in the world to require gender pay gap reporting from companies, including those with fewer than 250 employees. Of course, this is alongside Iceland who was announced to be the most thorough when it comes to creating a gender diverse nation, and they are believed to be the first to make equal pay mandatory for both private and public firms. Swinson’s roles as spokeswoman for Women and Equalities, and Foreign Affairs have meant she has seen first-hand, the disruption gender plays not only in parliament but in various areas of life from media to childhood and females’ bodies to work.

There is, however, one significant barrier Swinson has noticed, and examined, that stands between society and gender equality – Power. Swinson believes ending gender inequality remains a challenge while power remains in the hands of men in politics, business and culture. This issue of power – who has it and how they use it – is at the heart of this gender inequality, and underscore Swinson’s book. “A world of equal power is one where each individual is valued and can meet their own genuine choices, free of fear and the constraints imposed by their gender. It is not a world of conformity where everyone has to all be the same,” she writes.

We spoke to Swinson to discuss her recently published book Equal Power and to contemplate what we can do next from someone who is immersed in and dedicated to gender equality.

Why did you decide to write this book?

I wanted to share what I learned during the three years that I was the UK Government Minister for Women – in particular, the realisation that successful change to create gender equality needs a grassroots movement of individuals taking action in their everyday lives, and coming together to work on wider campaigns. Government alone will never be able to drive the significant cultural changes that are required.

How do you think the support in 2017 created change to individuals feeling safe coming forward and discussing issues?

Over the past few years, energy has been growing in the feminist cause. The #MeToo and #TimesUp movements we have seen recently have truly galvanised people into action. There is strength in solidarity, and supporting those who speak up, as well as speaking up ourselves are some of the most important things we can do.

Similarly, do you think these efforts are enough to create change in sexism and gender equality?

There is so much to do, and I would always say we need to do more. To me, it feels like we are at the beginning of a wave that is building. The more people lend their voices and take action, the sooner change will become unstoppable

Jacinda Ardern challenged the status quo when she announced her pregnancy and that her partner would be the stay-at-home father. Why are people so interested in this turn of events?

Society’s assumptions of gender roles around childcare and work are deeply embedded, and they underpin much workplace discrimination against women. It is always refreshing to see these stereotypes being publicly challenged – and not only for women. I am a strong believer in the hugely important role that dads play in their children’s lives, but it is often undervalued and dismissed. When I was a Minister, I changed the law in the UK so that mothers and fathers could choose how to share parental leave when a baby is born, which is part of how we can tackle the outdated views that see women primarily as carers and men as breadwinners.

You discuss how the parenting status of male politicians is much less likely to come under scrutiny. How does this scrutiny and sexism toward those in the public eye impact society?

One of the sad things that happens is that many women take one look at how women in the public eye are treated and decide they don’t want to go there. Whether it is the constant judgment of their appearance, the intrusive fascination with their private lives, or endless online abuse, it adds up to a sacrifice many are understandably unprepared to make.

You also talk about how sexist attitudes are ingrained into us from a young age, from toys to language in storybooks. Of these gendered assumptions, what surprised you the most?

One statistic that really struck me was how in the 1990s Disney Princess films, men had three times as many lines as women. These films are supposed to be about female heroines, and yet men have the agency. The nagging feeling we have that things aren’t quite equal is proven comprehensively in research, time after time – and it’s often even starker than our vague sense of injustice was suggesting.

Childhood plays such a pivotal role in gender equality and the messages and thoughts children grow up with. How can we bring children up in a way that encourages equality?

Little things can make a big difference. Think carefully about how you speak to children, what questions you ask. Don’t focus all your chat with girls about appearance, or assume that boys won’t want to read or draw. Whether it’s clothes, books, toys or activities, try to avoid gender stereotypes and offer all children a wide choice.

You state: ‘It’s as if the female body is so dangerous that it has to be closely controlled’ when discussing the Goldilocks paradox of women wearing too much/not enough. The woman’s body is a common topic when it comes to achieving sexism and equality. Why is this?

Our culture places a huge amount of women’s value in their bodies: their physical appearance, their sex appeal, their fertility. It creates a lose: lose situation for women, because the ‘ideal’ body is unattainable for most, and requires a huge cost of money, time and energy to even try to achieve. The violence enacted on women’s bodies is significant, from female genital mutilation to the frighteningly common sexual assaults and rapes.

How do you think we can achieve gender equality in the workplace?

We need serious leadership, an understanding of wider societal gender inequalities, and concrete action plans with targets and senior executives held accountable. It’s not purely a numbers game, but currently, it is far too easy for companies to produce some positive blurb about valuing women and not back it up with action that translates into tangible improvements. We need to rethink the world of work – from working hours to flexibility, and challenging the alpha male behaviour that is currently rewarded but which does not maximise performance.

When it comes to pay equity, why do you think businesses and companies (both private and public) should have to be transparent about pay?

What gets measured, gets done. Companies are driven by profit margins, KPIs, annual reporting benchmarks. Moving gender out of a fluffy category where everyone can say good things, and into the realm of bare numbers in black and white, helps to catapult the issue up the agenda. It is impossible to hide from the numbers, and often they even surprise the company leadership.

How do you think the way the world understands rape and rape culture has changed in the wake of Hollywood actresses coming forward and the resulting #MeToo movement? It is changing, but there is still a section of the public wondering what the fuss is about, or assuming the women are lying or trivialising their experiences. We had a big UK scandal in January where an elite corporate charity event was exposed for rampant sexual harassment of the women working there. Significant action is now being taken by regulators, but still, the Letters page of the Financial Times, which broke the story, showed the outdated attitudes we’re up against, referring to the women who were groped as “silly young girls”. We still have a long way to go.

You discuss how the media’s distorted responses to your comments about gender equality were an ‘inevitable part of the same endemic problem’. How have you noticed this in recent diversity-focussed movements?

There is still a high cost that many women – and men – face when speaking out about gender inequality. One British woman who reported inappropriate sexual advances by a UK Cabinet Minister was subjected to a campaign of character assassination by a major newspaper. We read about the actresses blacklisted by Harvey Weinstein, which Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson revealed had led to him not hiring them. The people choosing how we see the stories, who shape the lens of our media, are still overwhelmingly rich, white men.

A lot of people think that to achieve equality, we need to give women an ‘advantage’. Why are these thoughts harmful to creating change, and how can we educate people to see equality is simply that – equal opportunities?

I write about the invisibility of gender and how hard that makes it to tackle these issues. When people believe there really is equality already, that they are somehow immune to gender bias, then they perceive any move to support women as an unfair advantage. Obvious sexism is often easier to address, but the quiet, unconscious norms and assumptions are so baked into our culture, we can totally miss that they’re there. I hope my book helps people to see the issue, by laying out the evidence right across society – and then importantly, give people a toolkit for how they can start changing it.

You note how ‘we are all sexist, and so are our institutions and power structures’. How can we stop being sexist, as individuals?

The first step is awareness, seeing our own biases. Counting also really helps – transparency and data to keep track of where we are at, to cut through our unconscious assumptions. And we can structure recruitment, and employment processes to try to design out inequality, as Iris Bohnet so powerfully argues in What Works: Gender Equality By Design.

It has been said that 2017 was a watershed in the fight against sexism and inequality. How can we use this passion and drive for the better to create equal power?

We need to look back and celebrate our mothers, grandmothers and all the previous generations who fought for the rights we have today – rights to vote, rights to control our own bodies, rights to equal pay at work, and much more. Then we also need to look forward, to create a world where 50:50 is the benchmark. We must make sure the actions we take today – individually and collectively, little things and big campaigns – will lift up our daughters so that they can enjoy equal power.

WORK: The Unlevel Playing Field

In the chapter entitled Work, Swinson discusses the how gender inequality is impacted by the workplace: “Research shows that women are just as ambitious as men and women are the biggest underused asset for our labour market,” Swinson writes. One way in which Swinson suggests gender inequality is reinforced in the workforce is the culture in our ‘modern’ day workplaces which she writes were designed by men, for men.

Toxic Environment

The structural sexism in the workplace is not limited to issues around having children, however – that’s just one of the most visible and obvious parts. The culture, the norms, the experience of work is different for men and women, and it’s important to shine a light on all of this, too, because often people point to the challenges of combining work and family responsibilities and see that as a convenient explanation for the power imbalance between men and women.

Many firms casually attribute the lack of women in senior roles to women leaving after having a family, but this is rarely the full story. Women may leave the organisation, but as they typically do not leave the labour market, this attrition should be recognised as an indicator of dissatisfaction with a toxic work environment, rather than something inevitable.

I met Therese Procter for a coffee shortly before she celebrated her 30-year milestone with Tesco: not many people these days can mark such a length of service with one employer. Other than a short spell at the Bank of England as her first job after leaving school, Therese had spent her entire career at the supermarket giant, steadily working her way up through the ranks from an entry-level position to become Chief People Officer at Tesco Bank. She spoke with passion and authority on the importance of creating a genuinely inclusive working culture and the productivity gains that result, and the challenges of building shared values across staff when setting up a new institution with more than 4,000 employees from scratch.

I could immediately see how the warm, engaging and clearly determined, Therese had succeeded in leading others. Her mantra ‘be kind, be brave, be you’ seemed a pretty good piece of career advice. Yet I was stunned when she spoke about the career advice she had been given on her way to the top. She had been told to get elocution lessons, to make her hair ‘less big’, to change her wardrobe. Until she mentioned it, I hadn’t even clocked that she was from the east end of London – why should anyone care what accent you make your point in? She summed it up: ‘The advice I’ve been given to get on is to change who I am.’

Groupthink stifles innovation, while diversity of voices sows the seeds for better decision-making. When people spend valuable energy suppressing who they are and projecting a different persona – whether it is adopting a different accent, carefully choosing pronouns when discussing their same-sex partner, or fighting with their hair to make it ‘acceptable’ – they are less able to thrive. Workplaces need to let people be individuals.

On their own, the tiny slights that happen in the workplace seem almost not worthy of mention. But piled on top of one another, the compound effect is powerful. Clients talking to your more junior male colleague instead of you. The sexist ‘joke’ and banter in the office. Being talked over in meetings, the point you made ignored until a man says the same thing a few minutes later and is lauded for it. President Obama’s women staffers banded together to challenge this, adopting a tactic they called ‘amplification’. When one woman made a good point, other women would reference the same point, giving credit to the woman who first said it, so it was noticed rather than ignored and so that – importantly – the person who made the point would receive the recognition.

Everything is set up with men at the centre, from the corporate hospitality default of men’s sporting events, to the choice of speakers for company awards evenings. In 2015, the ill-judged ‘entertainment’ at the Construction Computing Awards led to attendees walking out and a social media backlash. The comedian they booked made sexist jokes about the few women in the room, then launched into a tirade of Irish jokes when challenged by a male audience member who happened to be Irish – exactly the opposite of the kind of culture construction needs to create if they are to plug the skills gap. Men and women alike expressed their disappointment; the organisers apologised and gave assurances that they would work hard to prevent such problems in future. But it’s worth noting how the action of the attendees affected the outcome in this situation. By challenging the sexism directly, voicing concerns online, and in some cases voting with their feet, men and women in this industry sent a powerful message.

Equal Power by Jo Swinson, published by Atlantic Books, distributed by Allen & Unwin, $39.99.