The World’s Best Wildlife Photography

In the words of the greatest poet and playwright in history, William Shakespeare, “One touch of nature makes the whole world kin.” The world is such a beautiful, marvellous place and we’re all so lucky to live within it.

Started by the BBC Wildlife Magazine in 1965 with 361 different entries, the prestigious event now receives up to 48,000 entries from 100 different countries worldwide. The images showcase the intense emotive power of photography and its advocacy of global issues.

The Wildlife Photographer of the Year, which is developed and produced by the Natural History Museum, London, awarded the grand prize to Yongqing Bao from the Chinese province of Qinghai, who captured The Moment, a slightly comical snapshot of when a Tibetan fox ambushes a marmot, which soon went viral. Kiwi 14-year-old, Cruz Erdmann, won the Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year with his image of a big fin squid drifting in the blackness of the ocean. Other winners allowed viewers to look closely at the immersive and infinite possibility of photography.

Land Of The Eagle by Audun Rikardsen, Norway

Winner 2019, Behaviour: Birds

High on a ledge, on the coast near his home in northern Norway, Audun carefully positioned an old tree branch that he hoped would make a perfect golden eagle lookout. To this he bolted a tripod head with a camera, flashes and motion sensor attached, and built himself a hide a short distance away. From time to time, he left roadkill carrion nearby. Very gradually – over the next three years – a golden eagle got used to the camera and started to use the branch regularly to survey the coast below. Golden eagles need large territories, which most often are in open, mountainous areas inland. But in northern Norway, they can be found by the coast, even in the same area as sea eagles. They hunt and scavenge a variety of prey – from fish, amphibians and insects to birds and small and medium-sized mammals such as foxes and fawns. They have also been recorded as killing an adult reindeer. But livestock farmers in Norway have accused them of hunting sheep and reindeer rather than just scavenging carcasses, and there is now pressure to make it easier to kill eagles legally. Scientists, though, maintain that the eagles are a scapegoat for livestock deaths and that killing them will have little effect on farmers’ losses. For their size – the weight of a domestic cat but with wings spanning more than 2 metres (61/2 feet) – golden eagles are surprisingly fast and agile, soaring, gliding, diving and performing spectacular, undulating display flights. Audun’s painstaking work captures the eagle’s power as it comes in to land, talons outstretched, poised for a commanding view of its coastal realm.

Canon EOS 5D Mark IV + 11–24mm f4 lens at 11mm; 1/2500 sec at f14 (-1 e/v); ISO 800; Canon Speedlite 600EX II-RT flash; Camtraptions motion sensor; Sirui tripod head.

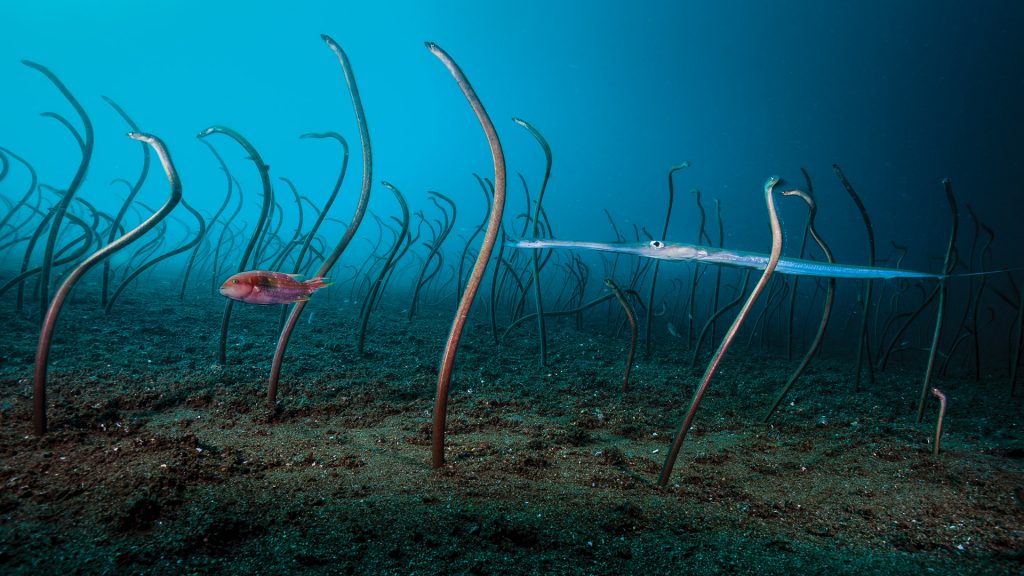

The Garden Of Eels by David Doubilet, USA

Winner 2019, Under Water

The colony of garden eels was one of the largest David had ever seen, at least two thirds the size of a football field, stretching down a steep sandy slope off Dauin, in the Philippines – a cornerstone of the famous Coral Triangle. He rolled off the boat in the shallows and descended along the colony edge, deciding where to set up his kit. He had long awaited this chance, sketching out an ideal portrait of the colony back in his studio and designing an underwater remote system to realize his ambition. It was also a return to a much-loved subject – his first story of very many stories in National Geographic was also on garden eels. These warm-water relatives of conger eels are extremely shy, vanishing into their sandy burrows the moment they sense anything unfamiliar. David placed his camera housing (mounted on a base plate, with a ball head) just within the colony and hid behind the remnants of a shipwreck.

From there he could trigger the system remotely via a 12-metre (40-foot) extension cord. It was several hours before the eels dared to rise again to feed on the plankton that drifted by in the current. He gradually perfected the set-up, each time leaving an object where the camera had been so as not to surprise the eels when it reappeared. Several days later – now familiar with the eels’ rhythms and the path of the light – he began to get images he liked. When a small wrasse led a slender cornetfish through the gently swaying forms, he had his shot.

Nikon D3 + 17–35mm f2.8 lens at 19mm; 1/40 sec at f14; ISO 400; Seacam housing; aluminium plate + ballhead; remote trigger; Sea & Sea YS250 strobes (at half power).

Early Riser by Riccardo Marchgiani, Italy

Winner 2019, 15-17 years old

Riccardo could not believe his luck when, at first light, this female gelada, with a week-old infant clinging to her belly, climbed over the cliff edge close to where he was perched. He was with his father and a friend on the high plateau in Ethiopia’s Simien Mountains National Park, there to watch geladas – a grasseating primate found only on the Ethiopian Plateau. At night, the geladas would take refuge on the steep cliff faces, huddling together on sleeping ledges, emerging at dawn to graze on the alpine grassland. On this day, a couple of hours before sunrise, Riccardo’s guide again led them to a cliff edge where the geladas were likely to emerge, giving him time to get into position before the geladas woke up. He was in luck. After an hour’s wait, just before dawn, a group started to emerge not too far along the cliff. Moving position while keeping a respectful distance – and away from the edge – Riccardo was rewarded by this female, who climbed up almost in front of him. Shooting with a low flash to highlight her rich brown fur against the still-dark mountain range, he caught not only her sideways glance but also the eyes of her inquisitive infant.

Nikon D800E + 16–35mm f4 lens at 30mm; 1/60 sec at f8; ISO 100; Godox V860II-N flash.

Night Glow by Cruz Erdmann, New Zealand

Winner 2019, 11-14 years old

Cruz was on an organized night dive in the Lembeh Strait off North Sulawesi, Indonesia and, as an eager photographer and speedy swimmer, had been asked to hold back from the main group to allow slower swimmers a chance of photography. This was how he found himself over an unpromising sand flat, in just 3 metres (10 feet) of water. It was here that he encountered the pair of bigfin reef squid. They were engaged in courtship, involving a glowing, fast‑changing communication of lines, spots and stripes of varying shades and colours. One immediately jetted away, but the other – probably the male – hovered just long enough for Cruz to capture one instant of its glowing underwater show.

Canon EOS 5D Mark III + 100mm f2.8 lens; 1/125 sec at f29; ISO 200; Ikelite DS161 strobe.

Snow Exposure by Max Waugh, USA

Winner 2019, Black and White

In a winter whiteout in Yellowstone National Park, a lone American bison stands weathering the silent snow storm. Shooting from his vehicle, Max could only just make out its figure on the hillside. Bison survive in Yellowstone’s harsh winter months by feeding on grasses and sedges beneath the snow. Swinging their huge heads from side to side, using powerful neck muscles – visible as their distinctive humps – they sweep aside the snow to get to the forage below. Slowing his shutter speed to blur the snow and ‘paint a curtain of lines across the bison’s silhouette’, Max created an abstract image that combines the stillness of the animal with the movement of the snowfall. Slightly overexposing it to enhance the whiteout and converting the photograph to black and white accentuated the simplicity of the scene.

Canon EOS-1D X + 100–400mm f5.6 lens at 200mm; 1/15 sec at f22 (+1 e/v); ISO 100.

The Huddle by Stefan Christmann, Germany

Winner 2019, Wildlife Photographer of the Year Portfolio Award

More than 5,000 male emperor penguins huddle against the wind and late winter cold on the sea ice of Antarctica’s Atka Bay, in front of the Ekström Ice Shelf. It was a calm day, but when Stefan took off his glove to delicately focus the tilt-shift lens, the cold ‘felt like needles in my fingertips’. Each paired male bears a precious cargo on his feet – a single egg – tucked under a fold of skin (the brood pouch) as he faces the harshest winter on Earth, with temperatures that fall below -40˚C (-40˚F), severe wind chill and intense blizzards. The females entrust their eggs to their mates to incubate and then head for the sea, where they feed for up to three months. Physical adaptations – including body fat and several layers of scale-like feathers, ruffled only in the strongest of winds – help the males endure the cold, but survival depends on cooperation. The birds snuggle together, backs to the wind and heads down, sharing their body heat. Those on the windward edge peel off and shuffle down the flanks of the huddle to reach the more sheltered side, creating a constant procession through the warm centre, with the whole huddle gradually shifting downwind. The centre can become so cosy that the huddle temporarily breaks up to cool off, releasing clouds of steam. From mid‑May until mid-July, the sun does not rise above the horizon, but at the end of winter, when this picture was taken, there are a few hours of twilight. That light combined with modern camera technology and a longish exposure enabled Stefan to create such a bright picture.

Nikon D810 + 45mm f2.8 tilt-shift lens; 1/60 sec at f11; ISO 800; Gitzo 5562LTS tripod + Novoflex CB5II ballhead.

The Moment by Yongqing Bao, China

Joint Winner 2019, Behaviour: Mammals

It was early spring on the alpine meadowland of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, in China’s Qilian Mountains National Nature Reserve, and very cold. The marmot was hungry. It was still in its winter coat and not long out of its six-month, winter hibernation, spent deep underground with the rest of its colony of 30 or so. It had spotted the fox an hour earlier, and sounded the alarm to warn its companions to get back underground. But the fox itself hadn’t reacted, and was still in the same position. So the marmot had ventured out of its burrow again to search for plants to graze on. The fox continued to lie still. Then suddenly she rushed forward. And with lightning reactions, Yongqing seized his shot. His fast exposure froze the attack. The intensity of life and death was written on their faces – the predator mid-move, her long canines revealed, and the terrified prey, forepaw outstretched, with long claws adapted for digging, not fighting. Such predatorprey interaction is part of the natural ecology of the plateau ecosystem, where rodents, in particular the plateau pikas (smaller than marmots), are keystone species. Not only are they the main prey for foxes and nearly all the other predators, they are key to the health of the grassland, digging burrows that also provide homes for many small animals including birds, lizards and insects, and creating microhabitats that increase the diversity of plant species and therefore the richness of the meadows.

Canon EOS-1D X + 800mm f5.6 lens; 1/2500 sec at f5.6 (+0.67 e/v); ISO 640; Manfrotto carbon-fibre tripod + 509HD head.