KITA: Songs That Speak

There’s definitely something unique about home-grown music that has been created unapologetically from the heart. Songs that are nice and comforting, like a warm cup of tea on a rainy day, or a billion songbirds harmonising together. Songs that speak from the ‘outside-looking-in’, or narrate on global issues, and have real punch, or oomph. The songs that are human and rich and raw. Wellington-based three-piece band, KITA is a power-house in creating any type of music that touches the heart. Whether it’s that cup of tea, or that ‘outsider-looking-in’, the songs resemble a unity that really pulls the listener in.

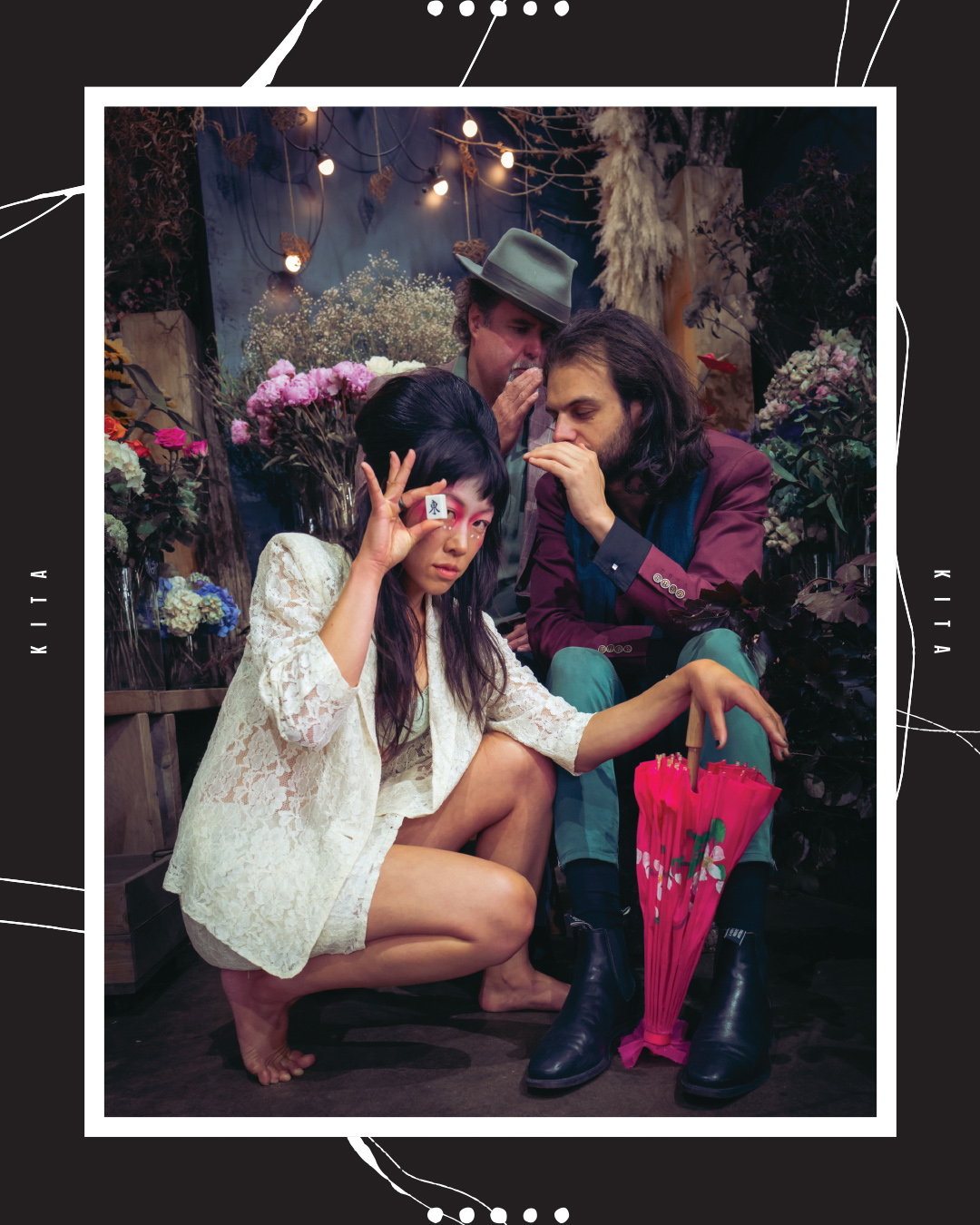

Born in Taiwan and raised in Auckland, Nikita 雅涵 Tu-Bryant moved to Wellington to study jazz at 18. There, she learnt the many valuable skills that she still uses today with her music, like the art of discipline and the importance of making connections. Whilst down in Wellington, she met keyboardist and producer, Ed Zuccollo and drummer, Rick Cranson. Playing keys for such bands as Trinity Roots, The Black Seeds and L.A.B., Zuccollo’s sound is one-in-a-million and Cranson’s crashing splash of colour on percussion reminded Tu-Bryant of her Pākehā father’s rock influence when she was a child. Together, their sound matched perfectly and KITA was born.

Having recently released their first full album together, recorded and mixed during Covid-19 lockdown by Grammy Award-winning producer, Tommaso Colliva between Wellington and Milan, the band recently toured their hotly anticipated album around the country.

M2woman had the opportunity to speak with Nikita 雅涵 Tu-Bryant on her music, the creation of KITA and the band’s latest album.

If you weren’t making music, what else will you be doing? What do you do in your spare time?

I try really hard to go surfing whenever there’s waves. I think, for me, having silence and being able to connect to natural spaces allows me to ‘stare at the trees’ for 10 minutes, and ideas pop into my head. Having that feeling of timelessness is important for mental health as well.

I like getting dirt under my nails. I love gardening and have built a little vegetable patch for my flat. I do a bit of painting too and a bit of theatre and film and writing too.

What was the journey like that took you to music?

I was a little Taiwanese girl growing up in Aotearoa. I was made and born in Taiwan. My mother is Taiwanese and my dad is from the South Island. My mum was like: ‘I’ll know what will make you really cool! Giving you a violin!’ Great, I thought, I can’t fit in with people already, so let’s make me more uncool, mum!

Having such culturally-diverse parents in New Zealand played such a pivotal role in why I do things the way I do. My dad, who was a bogan-biker—my mum came from a sheltered family, by the way—brought me up on Jimi Hendrix, The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan. I got introduced to the guitar when I was 10 or 11, but I wasn’t allowed to practice guitar until I practiced my violin. I started writing songs when I was about 12—pretty basic stuff. One of the first ‘proper’ songs that I wrote was called ‘Anywhere But Here’ and it was about my parents fighting. I’m sure they’re cool with me sharing this, because it’s the truth. They were always butting-heads about how to raise me. After writing this song, I was put in touch with a fantastic music arranger, Godfrey de Grut. At the time he was working with Elemeno P. He helped me arrange my music and entered me in for a New Zealand On Air grant, which I got when I was 15.

Back then, I didn’t quite understand how my song went from this really rootsy, acoustic style to this epically-produced pop song. At the time for me, in my mind, that was what selling-out was and that didn’t sit well with me. I didn’t want to just be that so I used the money for my band in highschool. The third time we entered Rock Quest, I won Best Vocalist and bought some turtles.

But I was just headed down that route; I didn’t want to be a ‘pop icon’. I just wanted to be in a band where I can play these songs and have more creative control. Now I realise that it wasn’t ‘selling out’. I think that now I can produce a strong core of a created thing and see clearly all the different ways it can be represented. Each of these representations can then communicate to different types of people.

I left Tāmaki when I was 18 and came down to Wellington to study at the New Zealand School of Music, which was very different. I didn’t really know what I was going to do. I had always done theatre and I had always done music. I was also the only one in my family who had really moved out of home. I was the one breaking new tracks. Going to the School of Music, which was quite jazzy, made me realise that I didn’t want to be playing jazz. It did equip me with incredible vocabulary that exists in how I communicate my stories now. It gave me opportunities for networking and the discipline of practice. It gave me the opportunity to move to Wellington, which is such a creative space.

Now, when I think about KITA, I see it as a space where these songs (born from weird, kooky places in my head that came from being excluded) can be completely inclusive. Not being super abstract so people don’t understand what I’m trying to say. It’s a space where everyone can be a part of it. Then there are other spaces where I can get weird and do whatever I want and be understood. In short, that’s where music has taken me.

The intention (of the new album) is to reflect, rebuild, feel uplifted, to reconnect. That in the sense of reconnecting to each other and with ourselves, with our natural environment.

How would you describe KITA’s music?

The best way is for me to describe the three personalities. Although KITA is named after my name, it is a band. My background is folky, it’s songwriter. I love narratives, but I really like enigmatic messages—poetry that you can’t decipher. I also really like minimal, beautiful and melodic guitar-lines. Pink Floyd’esque solos—not so ‘shreddy’. I ain’t a ‘shredder’, or a gear-head—I’ve only got two pedals!

Ed Zuccollo, our synth-master, plays a 30kg 1970’s Analogue Minimoog synthasizer, which he uses with his left hand. And he plays a 60kg Rhodes (not a Nord) with his right. He carries them to every gig we play! Ed really knows how to use his equipment. He takes us to space. Our music is bassey, euphoric and quite different to what we sound like in the studio. Rick Cranson, one of my favorite drummers in Aotearoa—he’s the drummer for Little Bushman—is 70’s psychedelic with big drum sections.

Ed Zuccollo is also a producer so our studio stuff goes into the electronic realm. But us, when we play together live, is a psychedelic-retro-pop with long sections in certain songs. We wanted to make a difference for our listeners between the live performance and listening to the album.

How was it working on KITA’s latest album?

Before Covid, through a series of beautiful synchronicities, international-manager from the UK, Seamus Morley—who used to manage like Leftfield and Above & Beyond—found us and flew over from New York to see us play in Wellington. A year before that happened, I had said: ‘I don’t want a manager!’ But alas, he came onboard, we recorded an EP and Tommaso Colliva (MUSE, Razorlight) came over from Italy and worked with us. It’s all thanks to Seamus that we got connected to Tommaso. He’s very down-to-earth, he just loves music and is such a good dude! He was the producer for MUSE for about 10 years!

We recorded in Wellington in The Armoury studios with Tommaso for our EP, and then luckily during the Covid window, we managed to tour our EP to three different places in the North Island. 80 percent of the songs for the album were written during lockdown, in isolation, and we wanted Tommaso to come record with us, but obviously we couldn’t! So get this, we were in The Armoury, once again, and we’re Zoom-ing Tommaso in real-time! In the 60’s in the studio, people wouldn’t believe that that was how we now record music!

What can audiences expect to hear from the album?

The intention is to reflect, rebuild, feel uplifted, to reconnect. That in the sense of reconnecting to each other and with ourselves, with our natural environment. There are a lot of themes in the album. Through the Trees is about colonisation, and Homefires is a love-song, so it felt apt especially with people coming home after Covid. Dig Deep was written during lockdown, and it was inspired by the drawer or the cupboard full of sentimental things that you know you need to be in the right frame of mind to go into.

There’s definitely social and political views presented (gently) in these songs, but I hope not in a way that would appear aggressive or shameful.

What does your creative process look like?

There are two main ways creativity happens for me. When I was younger, it was when I had space and silence and be curious. Also when things were going on in the world. Then, during lockdown, the creative process was totally different. Because there was so much idle time, Ed and I were like, ‘we need to write an album…’. We would give each other 20-minutes, pick a key, a tempo and disappear. Within that 20 minutes, Ed put together the bass and keys and I would write lyrics and a melody. When time was up, we’d put it together and boom. It was crazy. The track, Open Eyes was the first song we did during lockdown.

After Level 4 lifted, we got together and jammed in the studio again. In the song, Private Lives that bridge just came when we were having a jam. The song, Neverending Light, I wrote that song before lockdown, but the chorus was in response to Black Lives Matter. That connection that everyone is looking for.