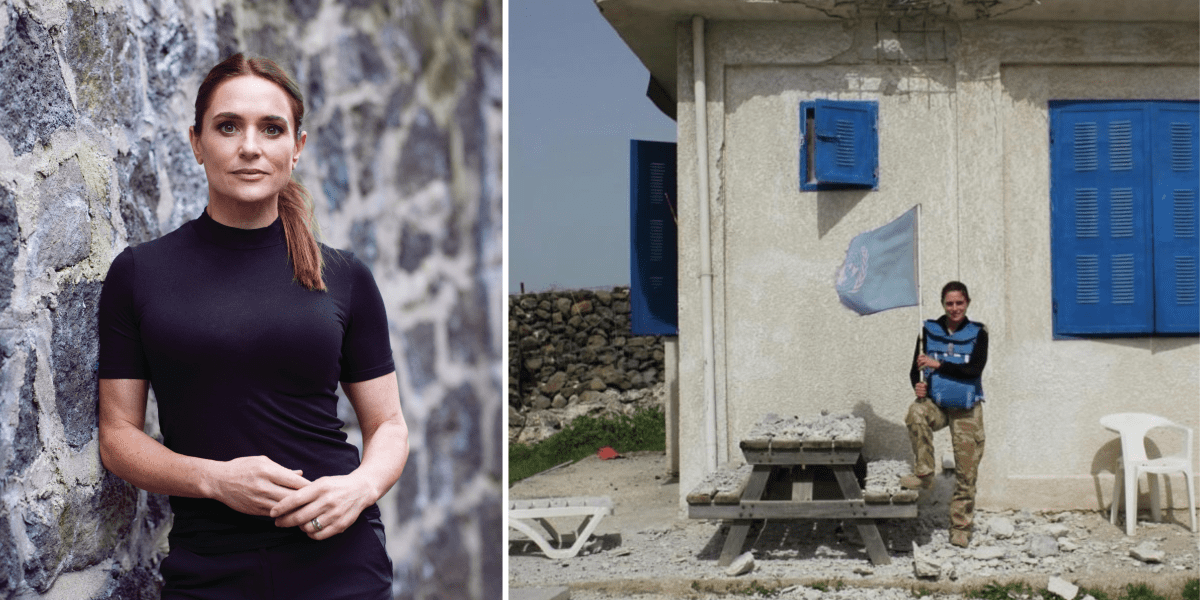

“The Resilience Toolkit” Is A Book Written After Being Kidnapped Working for the UN

There’s something timeless and universal about tales of individual tenacity and adaptability. They are inspirational for sure, but it’s maybe also that they provide a blueprint for navigating the intricacies and challenges of life. And resilience is not only a way to face adversity but it is a foundation for human potential. Dr. Alia Bojilova, an expert in peak-performance psychology, has not only studied this quality academically but has lived it.

From the politically-charged corridors of Eastern Europe in her youth to Syria, where she negotiated her own release from captivity, Dr. Alia’s life has been an exploration of the power of the human spirit. Now, in her new book, “The Resilience Toolkit,” she distils decades of professional insight and personal encounters into a transformative guide on ‘how to dig deep and explore life at the edge of possibility.

I want to start by sharing a sentence from your book, “We simply don’t notice the now as we are too busy dragging the echo of yesterday around with us.” I found that particularly moving but it’s also an example of the poetic and poignant writing throughout, did you get a sense when you were going through this process that you were onto something quite special?

I’m so grateful this sentence captured your attention. I appreciate this book the most because of the incredible stories and learnings it captures. It’s a careful collection of Post-it notes that have been collated all over the world on my travels and through countless experiences with some of the most remarkable resilience heroes I have worked with.

I do love what I do, I absolutely adore it and see resilience as essential for all of us. I feel as if every single one of my days engaging with the people I work with involves ‘aha’ moments worth capturing on a Post-it note and deserving of a book. I do remember the moment when I wrote this one, by the way.

Can you take us back to that moment? What was the thing that inspired that sentence?

This was one of my first trips overseas working as a member of the entrepreneurial community as a partner in a venture space that I operate. I noticed that the extraordinary talent we were working with was oftentimes preoccupied by unrelenting rumination and worry about the future. What was right there, in front of them was extraordinary. But what was staying in their way was the echo of yesterday and the stench of tomorrow, as we call them, the white noise that obstructs our ability to focus on the here and now, on the opportunity of the present moment.

My past experiences serving along with peak performers in environments like the military and peak performance sports, for example, had shown me that this level of distraction is unsustainable. You simply cannot thrive or operate effectively whilst being scattered across all these different domains. So, I do remember that flight distinctly because I realised that worry and rumination can sometimes drive us but they always take away far more than they give us.

A lot of us seem to carry around this echo of yesterday or this baggage but it would be so much more freeing if we could, as you suggest, just treat the day as a new opportunity or new chapters as new opportunities. What advice would you have for people to come to really start the morning and embrace the potential without being burdened by the weight of yesterday?

We have to accept that the weight of yesterday helps enable us, to a point. It stops us from making the same mistake twice. It grounds us but it doesn’t have to hold us still. This echo is designed to keep us aware, to stay mindful. But most of us take it a step too far. The vast majority of us choose to go on a walkabout with fear instead of exploring opportunities. This prevents us from experiencing the exact things that we were hoping to achieve or explore. We need to learn to view the gremlins of doubt on our shoulders, have a conversation with them, and put it aside knowing that they often serve no purpose other than the indulgence of fear. It’s impossible for us to put aside what we come with or what we have experienced. There is power in all our experiences, if we let them. What we do with our experiences can lead to entirely different outcomes. The best outcomes emerge out of conscious recognition of what matters most, out of harnessing learnings and all that comes with this present moment in the direction of our intent.

In terms of reflecting on the stuff that’s gone, it struck me that the outside of your book doesn’t mention you being taken hostage in Syria. But then I got to the chapter where you’re talking about the RSA and the soldiers from World War II who for the rest of their lives lived under the shadow of their experience. For some of them, it meant that they weren’t able to really live after that. Was that something that occurred to you in terms of your own experience?

Absolutely. It’s one micro-moment in time. And I guess in comparison to what most of the world experiences these days, but also historically, it’s insignificant. It’s capturing the lessons learned from it and moving forward that matters most. I think I had an acute fear of being defined by this one incident as opposed to using the learning that it had on offer to help broaden my capacity for life beyond it.

When you have this moment of complete uncertainty with your life in the hands of someone else, how do you turn that into a life lesson?

Do you know? It actually happened in the moments of it. The vast majority of military observers in our context, have conduct-after-capture training. In it you are taught the need to maintain dignity and decorum at all times if captured; to ensure that you are worthy of respect, so you don’t get treated in a way that causes greater pain for you. Our hostage situation taught me that if you allow yourself to see anyone, even if it’s your worst adversary as someone who deserves your respect, the dynamics can change for the better. You can sense that; you see it cross-contextually, cross-culturally. Tiny micro-moments in the way in which you engage with people and situations, how much and what attention you give them can create markedly different outcomes.

Another gift of our situation was learning the importance of not letting fear take you on a walkabout. In situations such as the hostage scenario, your mind is wanting to go crazy places in an instant. In fact, it needs to, right? It needs to consider how much this may suck, and how much it might hurt. But that’s a finite space. What is far more powerful is discovering that you can pivot your mind, pivot to opportunity, your moment into something meaningful and positive. We have the capacity to choose where we direct our attention and shape our outcome, no matter our predicament.

I think we all have moments that highlight this opportunity. Our hostage situation was thankfully unique, but we have all had at least one opportunity to notice the difference between traveling the garden path of fear, worry, and concern and pausing to realise – ‘I can design this’; ‘I can really shape this experience for myself.’

You talk a lot about the importance of curiosity but also how it tends to reduce when we have fixed views on people or events around us. At the same time, society seems to have become more galvanized ideologically. Maybe this is fueled by social media, but it seems like we can be quick to shut down ideas from the other side of the debate. Do you think, have we lost some curiosity along the way?

The job of fear is to lean you into biases, into negative assumptions that will keep you safe. I’m not surprised that some of us are losing some of our curiosity about some things. But it doesn’t take much for us to re-learn to explore more widely. I do understand that in some aspects of our life as a society and in our current highly pressured times, we may have lost some access to curiosity. But we have to be mindful that we are managing so much already. Curiosity requires cognitive and emotional space. It’s not something that you can force into a scope of thinking that is narrowed by fear and overwhelm. If you are locked into a state of mere survival or managing endless disruptions, curiosity can seem like an inaccessible luxury. It’s very difficult to be stressed out and curious at the same time. It just doesn’t work. The job to be done is to consciously focus on what matters most, pause and shift focus away from fear and into exploration of alternatives. Curiosity will always give you far more than fear or bias.

I don’t know if we as humans are becoming less curious. I think we are more preoccupied, but I think we can make abundantly greater space for curiosity in our time.

Also maybe preoccupied with negativity. People are talking about interest rates, they’re talking about inflation, there are very real, but it seems to be that a lot of us are kind of complaining about where we’re at.

I don’t know, maybe this is just us pretending that life has happened to us for the first time. I’m beginning to realise that human beings are amazing at complaining. This is how we normalize our discomfort. When I was growing up in Bulgaria, in the village I came from, there was this little bench where people would wait for their livestock to arrive every day from the pastures. And there’ll be a line of grandmas sitting there complaining about the cost of cheese, the cost of bread, the price of electricity. That is just the way in which we sometimes process the things that irritate us. Also (and sadly) complaining seems to help us connect with people far more easily than being a bouncy butterfly that finds positivity in everything. It makes us relatable.

The fact that we are dealing with things that are unprecedented many of our lifetimes, is a good enough excuse for us to find a reason to complain. But it’s all about reference points. The other day, we were chatting with a couple of my colleagues in Venture. We were talking about how acute the level of threat, change and instability is for young entrepreneurs. We did this freely until a colleague of ours, who had experienced the global financial crisis and who had parents who had lived through the aftermath of World War II, cautioned us to check our bearings. The level of perceived acuity we are experiencing is dependent on the angle we take, right? The short of it is, humans complain, hopefully, they shift away after they’ve spilled out the negativity and choose that there’s something better than us focusing on the negative. But also, whilst things are really challenging for us, I’m hoping that we have enough wisdom to recognize there is an opportunity for us to pivot ahead better than we have ever been. Maybe it’s my world. Maybe it’s the space I’m in. I see an abundance of opportunities for us. Again, that’s another one of those situations where it depends on the angle of the street you stand on. You change the context, and suddenly the message changes.

I wonder if there is kind of maybe a cultural or generational thing as well. If we look at the entrepreneurial world, it is so much a celebration of youth while we kind of cast our older people aside and we don’t necessarily take on and integrate the perspectives that they have about the economic cycles that they’ve been through, or what the price of bread was after the war or things like that. Is that part of it as well, where sometimes just taking on some of those insights would help shift our perspective in terms of what’s really important?

I fully agree with you. Let’s be the critical ones for a moment and consider that as a society, we have dislocated from a lot of the wisdom that comes from lessons learned in generations past. The wisdom that only happens when you have lived life. You are right, we are focusing on the bright, scary or shiny ahead of us without having an appreciation for the depth of wisdom that comes from the past. I think we are missing a few beats, but it doesn’t mean we’ve lost them forever, right? We just get distracted on occasion.

I found it very difficult to read the chapter about the father that lost his wife and daughter and the process that you went through with him to help him cope. Logically I could understand it, but emotionally it is unfathomable. I’m not sure how I could personally carry on in that situation. But the fact that he was able to carry on and also contribute so much to his community speaks to the remarkable resilience of the human spirit. Are you still surprised at how resilient we are?

Hugely surprised and not at all surprised at the same time. The most humbling realisation when you scratch the surface is that most people have a story that is hard to comprehend and they could have lived through. The acuity of some of the stories shared in the book is significant. But there are many more confronting content pieces that I did not integrate for a variety of different reasons. What surprises me is how every single one of us has confronted at least one enormous proposition in our lives; a seemingly unsurmountable challenge in one form or another, subjectively at least. Our resilience capacity astonishes me and it excites me. We don’t realise what we are capable of until the challenge faces us. The remarkable aspect of the case study you refer to is that this individual displays some of the most extraordinary levels of generosity, in terms of his ability to support others in their own recovery, following the most incomprehensible level of loss that I, at least as a parent and partner can imagine. So how he has been able to grow through this and what he has been able to achieve with it, just so that he can survive with hope is extraordinary. But we all have this potential. We just have to choose to lean into it more often.

I’m struck by not only the depth and the sophistication and the nuance of the human spirit, but then also the basicness of it as well. You talk about these really primal responses to what we perceive as stress. Back in the cave days, it will be a sabre tooth tiger but today we conflate that with a public speech or something that we have to do. So much of us is still a bundle of really basic biological responses.

Absolutely. I think often in the best way possible too. You know, the beauty of this is that we have practiced the good stuff we need for resilience longer than we have the stuff that takes away from it. The fact that we are wired for thriving, and can witness the difference that people experience when they reconnect with the fundamentals we need to be healthy and well is hugely encouraging. We’ve got all the components to the magic of resilience.

What’s one of the most important takeaways that you want people to get from your book?

The starting point to this book was a simple heuristic- a rule of thumb called ‘Mind, where your mind goes’. I tried my hardest to extract a handful of snippets from all the amazingness I’m surrounded by in my work. I really do love this one heuristic though, especially for times when we are allowing ourselves to remain flustered, scattered, burnt out, threatened, worried, and disheveled. We are all experiencing some version of a hangover at the moment- the covid hangover, the economic crisis hangover. This messaging can totally screw us up. I think there’s a real possibility of us indulging in the negative narrative and missing the whole point, which is, you have a choice. You have a choice of where you focus your attention and how you engage with opportunity, no matter your predicament.

I firmly believe that there is always something you can do about your proposition, about your predicament. It doesn’t have to be an enormous stretch. If you focus on minding where your mind goes, and notice that there is a possibility to choose one tiny bit better, 1% better, something different for you to focus on that subjectively inspires, excites, and gives you a sense of purpose things change. That connection to the present moment becomes more meaningful and therefore hope becomes more accessible. Through connection, exploration becomes more accessible. Through exploration, you may suddenly realise that if you lift your head up away from the perceived white noise, there is an awesome space for you to play in.

Click here to find out where you can grab a copy of The Resilience Toolkit