Strange Attraction

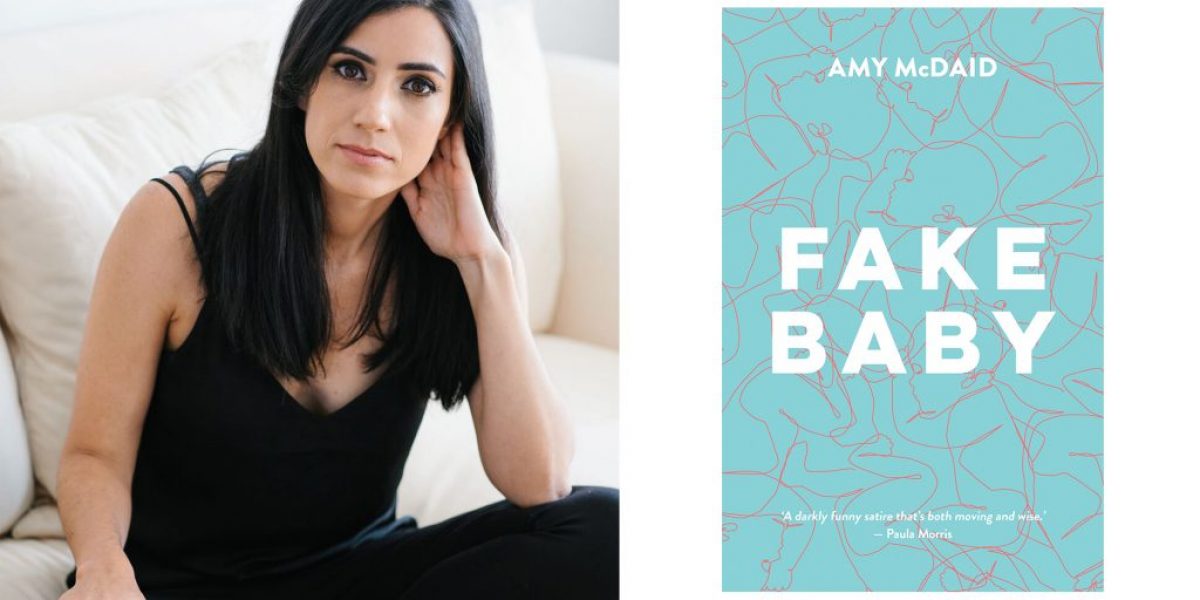

Fake Baby. The title of Amy McDaid’s debut novel – the draft of which won the Sir James Wallace Prize in 2017 – drives darkly yet comically at those tragic moments of relief and reprieve in escaping the stark reality of life-altering loss, along with the relatable drudgery of daily disappointments in tow: the theft of a lifelike doll called James, the deluded burden of a dead father threatening to destroy the world, and a pharmaceutical error that caps off one of the worst weeks of an all-round nice guy hurtling into middle age. Amy shares with M2woman her insights into her artistic process, the future of writing and her definition of success.

Was there a specific experience that made you want to write Fake Baby?

No, not a specific experience. Fake Baby is to me, primarily, an act of imagination. Though I guess in a way, the paths my imagination chose to take reflects a culmination of experiences: my work as a Newborn Intensive Care Nurse, the suicide of my brother and being witness to grief at a young age — particularly that of my Mother’s.

Then there’s my own experience with depression and anxiety, and my time spent with people experiencing mental distress. All of these things have helped build my empathy for people who are struggling or on the margins of society — like the three characters in Fake Baby.

Did you imagine as a child that you would be a novelist someday?

A favourite teacher told me I’d be a writer when I was eight years old and I believed him. I’ve always loved books and hoped one day I would write a novel. It just took a little longer than I thought!

What is the most difficult part of your artistic process?

For me — the generation of the idea and not knowing if it will take or not. That first draft where you have a limitless number of choices, right from character’s names to where they live to what they will do and what conversations they will have. It’s slow and torturous. Before Fake Baby, I worked for six months on a novel that I ended up discarding because it wasn’t working.

Once that first draft is done, and you have the sense you have something that works, you can get down to the best part of the process: editing. Which sounds awfully boring but I love it. My mentor Paula Morris likens it to knitting. This gentle repetitive process of combing sentences and rewriting and sharpening is like undoing a stitch, and sometimes you have to undo half your work to get to the mistake. But it’s so satisfying.

Your book sets the lives of three oddball characters in motion over nine days in one city. How did you settle on this structure for the book? Do you have a favourite chapter?

Honestly, I think I originally decided to write with three characters because I wasn’t sure if I’d have enough material for one, and I’ve also always been fascinated by the connection/disconnection we establish with strangers. I liked the short time frame because it allowed me to immerse myself in the daily lives of the three characters. It’s also a mirror; Jaanvi’s son lived for nine days.

I like the chapter when Jaanvi and Mark go to a restaurant together — it’s their first dinner out since before their child died. Mark is stressing about the expense, so Jaanvi in a passive-aggressive manner takes to ordering the most expensive beverages on the menu. The emotion is augmented when they are interrupted by Mark’s unpleasant fluoro-clad work colleagues.

We’ve all seen couples in restaurants that clearly aren’t getting on — it’s such a common situation. I’ve been there myself, I have to admit, and it’s a painful thing that can also be oddly funny (usually in retrospect!).

Arguably much of fiction is written with some relationship to facts. Is the novelist bound by any ethical or moral constraints, or is any story fair game for an artist?

We are becoming increasingly aware now of the dangers of cultural appropriation; this is perhaps the largest ethical constraint. Writers have an immense responsibility to the people their stories represent, and must seriously consider their motives if they want to tell a story centred in a culture outside of their own. The question a writer needs to ask: am I the best person to tell this story? Stories have power, they can add or detract from stigma and stereotype.

Morally — well what is moral? It is a fluid thing, determined by society. The work of Ginsberg, Flaubert, Henry Miller, were once considered immoral. A writer’s obligations are not towards producing a moral work, but producing a work that demonstrates honesty and intellectual courage while maintaining accountability.

When developing your characters, and writing about perspectives that are different from your own, be it gender, class, sexuality, race or ethnicity, what is your process here?

I climb inside my character’s heads, I talk to them; we have conversations. I ‘see’ them out and about and observe them; their way of walking, how they interact with the world. I need to immerse myself in their backstory — even if it doesn’t make it to the page — so I can understand what has shaped their views, their personality, their complexity. But there are limitations here, because if I tried to climb inside the head of someone too different from me, particularly from a different culture (to come back to cultural appropriation) I would not be able to do this successfully. This is the reason I made Jaanvi occupy that middle space between being white and brown: she is like myself, with both European and Rarotongan descent.

Stephen, who is so very distressed, represents in some ways my own state of mind and ways of thinking. But climbing inside his head was the most difficult; I found myself becoming disconnected and paranoid. In this way, writing can be like acting, where you take on a persona. Yet Stephen’s reality is still very different from my own, and I strived to be sensitive to that while not patronising him. I read widely — first-hand accounts of people who’d experienced extreme mental distress. I had several intelligent beta readers with good comprehension of mental health issues. A mental health advocate read chapters and I also talked to my brother about some scenes, as he has been a mental health service user.

There’s a wry, dry humour and an irreverence that comes through in your writing. Does this become a way to feed in more serious issues?

I love dark humour and using it appropriately is a great way to take the bleak out of dealing with serious topics such as grief. A friend said to me recently I had a heightened sense of the absurd, and I think she’s right.

Have these unprecedented times of pandemic and systemic issues influenced what you might write next?

I started my second novel before the pandemic unfolded, and it will probably be set prior, so I don’t think it will have a direct impact on the storyline. But then — these things do have a way of sneaking themselves in, don’t they? Even when you’re not conscious of it. So I’m sure there will be an influence there, however microscopic, because I’m writing contemporary fiction, and our world — how we perceive it, how we interact with it — is now different for COVID-19.

In one sentence: why do you write fiction?

To escape.

What is your favourite under-appreciated novel?

I’m going to take a different tack here, and say short story collections. I was in a bookshop recently looking for Ottessa Moshfegh’s genius Homesick For Another World and the bookshop owner confessed to me they don’t stock short story collections because they are a hard sell. This is such a shame!

Short stories are an incredible form, and so difficult to get right. Every paragraph, every sentence has to work hard; there is little room for the extraneous and subplots. As the master of the short story, Deborah Eisenberg, tells us, they are a “stranger, more volatile and more evanescent sort of thing”. I’m determined to read and write more of them over the coming year.

You are also a neonatal intensive care nurse. What drew you to that field and in what ways has it influenced your writing?

You are also a neonatal intensive care nurse. What drew you to that field and in what ways has it influenced your writing?

I was tiring of my job in adult health, a colleague said NICU was a great place to work, there was an advert on the intranet advertising a position vacant, I applied, and there you go! I really enjoy the challenges of caring for extremely preterm infants and supporting families through their NICU journey.

When a baby dies in NICU, it hits all of us hard, and though we are there for perhaps the biggest moment in that family’s life, we don’t often get the after story. How do the parents and family manage their grief? Are they supported? Does the relationship survive? In a way, Fake Baby was a way for me to explore this.

It is not uncommon to hear, you can only be a writer if you can afford it. Is this an irreconcilable dichotomy that cannot evolve with the times?

I’d say most writers can’t afford to write, but we do it anyway and we sacrifice a lot in order to do so. (Almost) everyone can afford a pen and paper. But not everyone has the luxury of time and space that writing requires.

Can it evolve? I believe it can, and it must. Stories are part of the fabric of society, and if we do not compensate our storytellers, then we lose out when they are forced into other work. The Public Lending Right scheme that compensates writers for library lending is an important source of income for writers and it has not been increased in ten years. We also do not receive any payment for e-books or audiobooks under this scheme. It’s a struggle even for well-established writers with multiple books out to make a living.

What is your advice for aspiring writers?

Turn up. Every day. Sit in front of that computer or hold that pen. Even if you don’t write a word. Keep on turning up. If you don’t do that, it can’t happen.

What is the best advice you have ever been given?

Turn up.

How do you define success?

I know how I don’t define it — and that’s with money and material possessions. Beyond that, it gets murky. I could say doing what you love, which was for me the definition of success for a long time, but there’s an aspect of privilege there that’s not an achievable reality for everyone, and that doesn’t mean you’re less or more successful that someone else.

So perhaps for me, success comes down to doing what’s important for you. Whether that’s creating, or a career, or providing for your family, or staying healthy. Sometimes, success when you’re struggling is much less: getting out of bed, getting the kids to school. Making them dinner. Success is being kind to yourself, and others.

What’s next for you?

Hopefully my second novel in three to

four years.