Traditionnelle Family Values

Allan and Catherine Scott haved helped pioneer not only the Marlborough wine industry but also a New Zealand one. With 40 years in the industry, they have helped shape the winemaking landscape and helped it reach a global consumer base. Launched over 25 years ago, their family business, Allan Scott Family Winemakers has become not only an iconic New Zealand brand but the foundation of a family business that has carried on to the next generation.

We talk to Allan and Catherine’s son, Josh Scott about stepping into his father’s shoes, the future of winemaking and making a Méthode Traditionnelle named after his mum.

You’ve grown up with the vineyard but does it feel like a transitional period at the moment with you taking on a more leadership role?

Yeah, especially being in a family-owned company. You’re grass roots up and I always say the most amazing thing about the wine industry is one day I could be literally digging out a drain and then the next day I could be in New York presenting our wines at one of the most famous restaurants. So there’s that real contrast and you really see your product from the grape, right through to the finished product.

The other thing I think is really interesting, about Allan Scott wines especially, is that you’ve got a really intimate knowledge of your wines. So, like this bubbles, I know the vineyard where it came from, I know what the vintage was like. You’ve just got a really good idea about everything behind it. It’s like when people talk about a wine; being able to talk about the vineyard and even understanding those vines; you have a really intimate knowledge about your product. And yeah, it makes it a lot more enjoyable.

When you’re talking about that, the process and the fact that every day you could be doing something different, is there one thing that you really enjoy the most?

The thing I enjoy the most is actually the tasting. I also like to try new things. The wine industry is pretty linear and everyone’s doing the same thing. So I love to push the boundaries; to try different things. And some of those new style wines coming out; the natural wines, and the orange wines, are really interesting.

And in terms of that experimental side, how does that work with your Dad? Does he let you push the boat out?

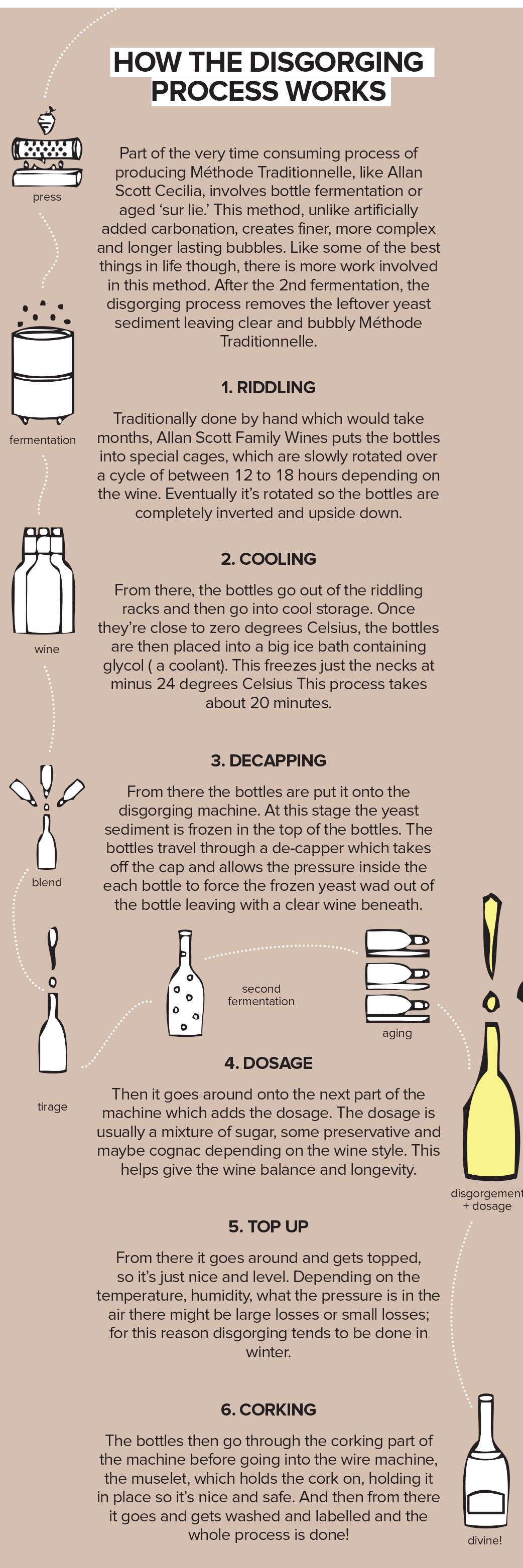

Yeah, Dad’s very much a traditionalist so I’m always getting into trouble for anything I do from everybody. But you have to keep on evolving I think and trying to do new things. Ninety percent of them don’t work, but there’s always the one that does. The bubbles is the perfect example. We did it for a reason, but we ended up buying a whole lot of equipment with the Allan Scott Cecilia Méthode Traditionnelle that we probably wouldn’t have and played around with the whole disgorging part, even driving around the vineyards to settle the lees. That sort of helped us where we are today with our equipment.

So, some of the innovation may not be doing something completely new but it’s doing things in a slightly different way. And that just makes it more exciting and keeps you thinking about how you can constantly improve.

There’s obviously a huge investment in terms of the equipment for disgorging and then also an investment in time to produce Méthode Traditionnelle. Was there a part of you that thought maybe it’s just quicker to do bubbles? Carbonate some wine and be done with it?

I’m a little bit of a purist in some sense. I do like doing things the natural way, as natural as possible or the traditional way in the sense of making bubbles. When I was involved with a Craft Brewery, that all was initially natural carbonation. I just think it gives it a bit of a nice mouth feel. But anything that moves away, or makes the quality less, I’m not a big fan of. It’s a hell of a lot easier just to force bubbles into it but this way here, you definitely get a superior product.

It gets better with age and I think that’s really, really important in that whole process. Even though it’s heinously expensive and takes a heinous, heinous amount of time and takes a lot of effort, the product at the end is something to be proud of. Especially with my mum’s name on it. (Laughs)

To go back to one of your passions, how do you define the difference in tastes and the difference in quality between something like this and more artificial bubbles?

I think the difference in quality between artificial carbonation and natural carbonation, especially if you are making it under the Méthode Marlborough parameters, is that aging. So you get that yeast development where you get some yeast character through in the wine and that’s really obvious. Whereas a lot of the cheaper ones have just this fruity, fruit bomb.

The mouth feel, the texture and the bubbles that are in ours are really small and elegant and they give this lovely finesse to the wine that you don’t get with artificial carbonation. The other thing is also the longevity of the wine; these wines will age really, really well. So even after they’ve been disgorged they will age for years and years, whereas a lot of those artificial carbonation ones don’t.

Can you explain what Méthode Marlborough is?

Allan Scott is part of Méthode Marlborough which is an industry initiative of Marlborough growers who’ve come together to make and promote Méthode Traditionnelle. It’s relatively simple to be involved with it; there are just three key parameters. It has to be aged in for 18 months “Sur Lie”; so aged in the bottle, which helps give the wine those biscuity characters

It has to be 100% Marlborough fruit, so you can’t have in 5% of something from a different region or anything like that.

And it also has to be the three traditional varieties which is Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier. They’re only those three varieties that can be involved in it, but most people are using Chardonnay and Pinot Noir here in Marlborough.

So why is it so important for the region to have these parameters?

The reason it’s important for us to have those rules for Méthode Marlborough is because there’s so much artificially carbonated wine on the market and it’s very hard to differentiate. You could go to your fine wine bottle store or the grocery and you see these products side by side and you assume it’s Champagne, or Méthode Traditionnelle as we have to call it in New Zealand, but it’s not. The quality difference is very noticeable. I even think people who are elementary drinkers could tell the difference between those two styles.

So this is really important to help educate the public, but also give people a better understanding of why they’re spending $25+ on a good bottle of sparkling wine, instead of buying something for $10 – there’s a reason why it’s $10. And that does sound snobby, but it’s probably a bit like Pinot Noir; it’s very difficult to buy a $10 Pinot Noir. But if you’re paying $30, you know you’re getting something fairly decent and Méthode Traditionnelle is very much similar to that.

Is it difficult to get that support with your local industry to follow the parameters of Marlborough Méthode?

Some of the pioneers in the Méthode Traditionelle industry have been putting this together for Marlborough and helped to try and build a profile so people could understand what real bubbles is. I think they are starting to make some headway and there’s been some exciting tastings and promotions to promote Marlborough Méthode.

I do think it’s important because it sets the standard so when people see that symbol, see Méthode Marlborough, they understand what it is, how it’s made and it’s a quality stamp. That’s really important for the industry here in Marlborough.

Your parents are some of the early pioneers in the industry. Do you feel a weight on your shoulders? A weight of responsibility?

I don’t. I’d hate to be the generation that stuffs it up. So there is a bit of expectation there to make sure that we can carry on their good name. Dad’s a really loyal person, Mum and Dad both were really loyal people and have a lot of friends and are good to our staff.

You really want to sort of keep that ethos going in the company, but really not to let anyone down and making sure we’ve got a good quality product. That’s probably the key thing. We always say this every tasting, it’s not just marketing propaganda, but every single bottle of wine that’s got the Allan Scott brand on, we want to enthusiastically stand behind and promote and be proud of to pour to people.

If we can’t do that, we wouldn’t put our name on it. And that’s really, really important. That’s a standard we’ve continued on.

As a kid, was there any sense of pressure about getting into the family business?

No, there definitely wasn’t. Initially, I wanted to be a marine biologist, but winemaking was easier. From a young age I’d been working in the vineyards. I always remember my very first taste of wine. I would’ve been in my teens, early teens, probably younger – I didn’t even know what the wine was. It probably was a bubbles because I remember tasting the yeastiness, I remember thinking it was like vegemite. Once I made that association with wine, I’d sort of clicked into it and I really became quite fascinated by it. Taking something so simple that could be quite complicated in the end of all those different flavours, it sort of sucked me in really.

It’s a fun industry to be in. As I said before, seeing your product from the vineyard right through to when you’re selling it, is pretty unique and pretty special. And every year’s different. I’ve been involved with the beer industry and it’s basically same old, same old. You’re brewing the same old beer, nothing changes. But in wine, the harvest changes. There’s heaps of different decisions you have to make and each vintage is very, very different. Every year it can be exciting, or it could be depressing, or it could be fun, or it could be boring, but the next season’s going to offer something different. That’s what’s so enticing about the wine industry.

How would you describe yourself as a leader in this industry?

I’m definitely a lead by example person. I’m not a motivational speaker, but I like to get in there and do it myself. People can see me on the bottling line, or working the harvests, or pruning, or driving a tractor. And then hopefully people go ‘Yep, if he can do it, then we can do it as well’. So I’m not really great with motivational speaking or paperwork, all that sort of carry on. It’s more just doing it really.

How would you describe your Dad as a leader?

He’s probably very much the same, he’s always led by example. He’ll be in here with a broom cleaning floors and bits and pieces. That’s probably the worst job in the winery, but everyone sees him doing it and then they’re not going to sort of scoot away from it, because those jobs are really important for the cleanliness of the winery. If you’re keeping your drains clean, you’re keeping your presses clean, you’re keeping your bottling line clean and that ethos flows through.

Is the legacy important to you?

That’s a really good question, I don’t know to be perfectly honest. At the moment I’d say no, but I’ve got children of my own, maybe when they’re older I think it would be. I know to my Dad it’s really important. But the industry’s so young here. A lot of the harvests I worked overseas had 10, 12 generations and legacy was massively important.

Gosh, we were over in Japan not so long ago and they had sake brewers with 40 generations, it was ridiculous. At the moment, I’m not too sure because the wine experience is so young here. But if this could maintain a family-owned business and eventually one of my children came through, or one of my sister’s children came through, that’d be great.